Read a New Essay by Machine Listening. Also: Jennifer Walshe’s Book "13 Ways of Looking at AI" to be Published by Unsound

Unsound London and Unsound Brussels Coming Early 2025

One of the reasons we started this Unsound Substack was to publish a long essay by Jennifer Walshe called 13 Ways of Looking at AI, Art & Music – a piece of writing that remains timely, funny, and eminently readable. We regard it as one of the most incisive pieces on AI and art and music, which is why we’re publishing a hardcopy version of the essay as a book, beautifully designed by Eurico Sá Fernandes and Wooryun Song. The book will be launched at London ICA on January 16, but you can already pre-order via the Unsound Bandcamp page.

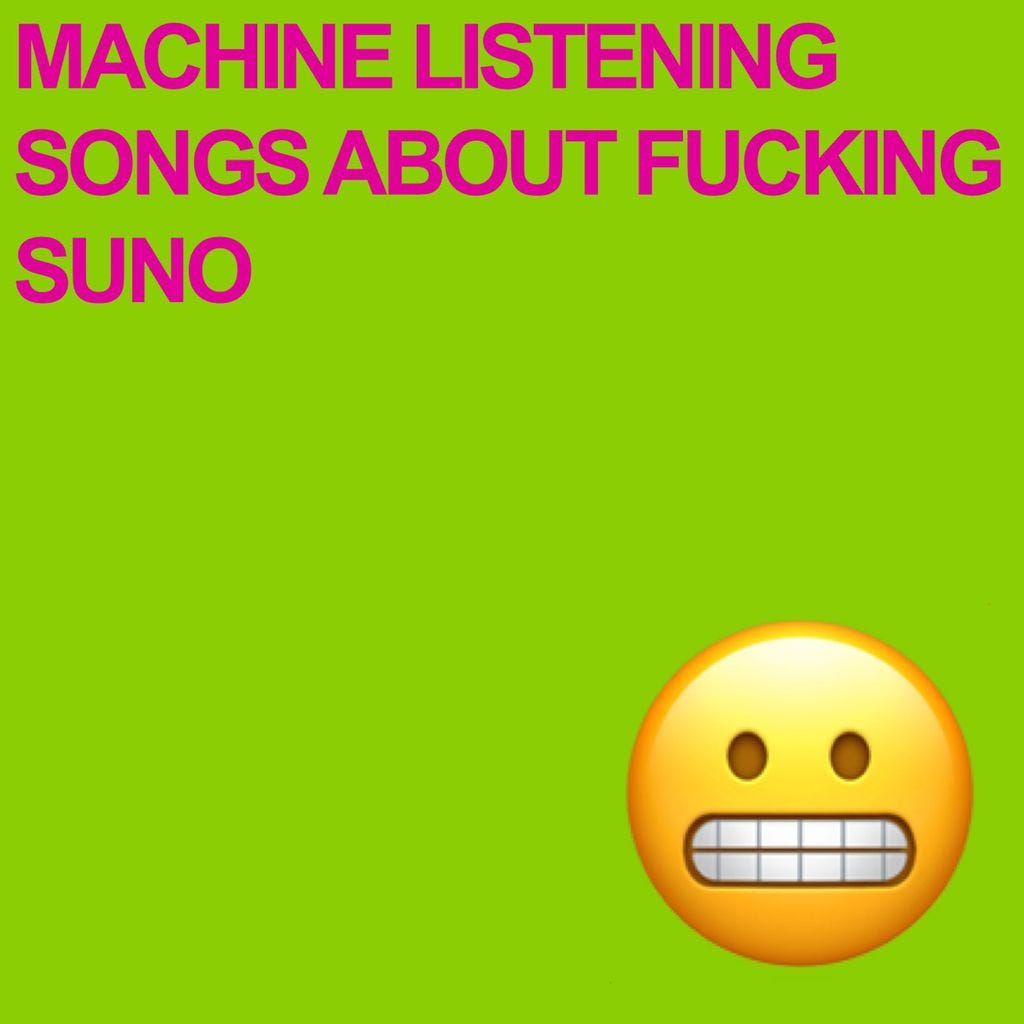

Today we’re publishing an essay by Machine Listening (Sean Dockray, James Parker, Joel Stern) that accompanies their just-released album Songs About Fucking Suno; it might also be regarded as a companion piece to Jennifer’s essay. You’ll find it below.

A lot has happened since the last edition of the Unsound Dispatch – we completed our flagship Unsound edition in Kraków, as well as Unsound New York. We’ll post a longer reflection on what has proven to be a difficult and intense year. 2025 promises to be just as packed, and, despite the major struggles that independent arts organisations like ours battle daily, we are looking with hope into the next months, with Unsound events coming early in the year at the Barbican in London, and in Brussels presented with Bozar. This edition of the Unsound Dispatch also contains info and ticket links for these events.

All the best for 2025 – may the New Year bring you adventures sonic and otherwise.

Mat Schulz and Malgorzata Plysa, Unsound Directors

Unsound London at the Barbican and ICA

Unsound returns to the main hall at the Barbican on January 17, with a program featuring composer Mica Levi, presenting a selection of pieces for large-scale string ensemble, including a new UK premiere commissioned by Unsound, and performed by Kraków’s Sinfonietta Cracovia; Guatemalan cellist, composer and vocalist Mabe Frattil; and Polish guitarist and composer Raphael Rogiński. Tickets are still available via the Barbican website.

A day earlier, on January 16, Unsound will team up with ICA to present a talk by Jennifer Walshe on 13 Ways of Looking at AI, Art & Music, part of the London launch of the book of the same name. Tickets available here.

Unsound Brussels at Bozar

On February 14 and 15, Unsound will land in Brussels to present a program with Bozar, taking place at Bozar and Reset, The lineup features Piotr Kurek presenting Smartwoods, with visuals based on paintings by Tomasz Kowalski; Aho Ssan & Resina’s Ego Death; Raphael Rogiński with Indrė Jurgelevičiūtė presenting Žaltys; Heinali & Yasia presenting Гільдеґарда; AKA Hex with Aïsha Devi & Slickback; and Rainy Miller’s project Joseph, What Have You Done?. The club program at Reset features the likes of 2K88 b2b ojoo, Slikback and gummi – with more to be announced soon. You can find ticket links and all info on the program here.

Unsound Brussels joint effort by Bozar and Unsound, with the support of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute.

Songs About Fucking Suno

by Machine Listening (Sean Dockray, James Parker, Joel Stern)

This essay accompanies an album of the same name by the research and artistic collective Machine Listening (Sean Dockray, James Parker, Joel Stern). The album and the essay are both about fucking Suno, but in different ways. You could think of the album as digital liner notes in a post-liner notes age. Or maybe they’re just two perspectives on automatic music generation. Songs About Fucking Suno was originally commissioned by Soft Centre, for performance in a library, and eventually realised at the Victorian Trades Hall with improvised vocals from the incredible Jennifer Walshe and Tomomi Adachi. But the album comes out of a longer collaboration with Unsound, which began online in 2020 and led to a residency and the first iteration of the Machine Listening Songbook: Dada/Data at Unsound 2023. Songs About Fucking Suno is available on Bandcamp and hosted on the usual streamers, like a virus. With thanks and apologies to Big Black.

2024 was the year automatic music generation broke.

Artists have been working with music made by generative AI systems for years, of course, but none of it was particularly popular. This is because, until 2024, most music being made with generative AI was still all about the strange and highly specific shittiness of generative AI as a medium. Jennifer Walshe has been the master of this compositional strategy, which owes as much to Situationist détournement as 20th century conceptual art. Across works like Ultrachunk (2018), A Late Anthology of Early Music (2020) and Ireland: A Dataset (2020), her output has consistently pointed to and expanded on the many ‘glitches’, ‘errors’, ‘gunk’, and other idiosyncrasies of the systems used to produce it. To someone like Walshe, whose background is in experimental music, artefacts like these immediately present themselves as new artistic material to imitate, compose and improvise with. And this is what gives her music its aboutness. Walshe’s work often feels exploratory, or even forensic: like she’s investigating and attempting to show us something about the neural networks she works with. ‘We are still at the point where art made with AI is art about AI’, Walshe explained in a brilliant essay from late 2023 (being launched as a book on Jan 16 at the ICA). And at the time, she was right.

Another good example from the ‘before-times’ is Dadabots, who Walshe collaborates with, and whose infinite metal machine music sounds like a neural network having a mental breakdown. One of the group’s first releases, Puzzlomaly (2017), is rigorously process-based AI conceptual art: the kind of musical experiment (like so much musique concrète and early computer music before it) that belongs as much in the research lab as the concert hall or gallery. The album’s three tracks were all ‘generated autoregressively with SampleRNN, a recurrent neural network, trained on raw audio from the album Ideas of Reference’, by the US mathcore band Psyopus. ‘The machine listened to the album 29 times over several days’ and generated 435 minutes of audio, of which Dadabots then selected and edited together a few sections for release. Does the album sound ‘good’? Not really. But it’s weird and interesting. It feels like a logical extension or even a kind of completion of mathcore as a project: its reductio ad absurdum. And without the slightest aspiration towards the mainstream as a result.

Lee Gamble’s Models (2023), by contrast, makes for much easier listening, and fits right in at Hyperdub alongside other ‘prestige’ electronic releases. But this isn’t really club music either. And it’s also not ‘about’ club music in the way Burial’s early releases often were. The clue is in the title. Models is still AI-generated music about AI music generation. It’s just been laced through Gamble’s characteristically lush but sombre production. Gamble was very clear about this in his interviews around the record’s release. What he found most intriguing about the AI systems he worked with, he said, were ‘the failures, the stumbles, the falls,’ which he leaned into as a result. Musically, Models seems to thematise the hauntological qualities of the degraded synthetic voices it employs. The voices on the record don’t sound human, but they don’t sound robotic either. The effect is more like an AI system trying to remember what a human voice sounds like. The voices sound feeble and murky: like they’ve been dredged, not engineered.

AI generated music isn’t like that anymore. On Ghostwriter977’s ‘Heart on my Sleeve’ from April 2023, the vocals are already much slicker and more stable. And it’s only because they were deliberately modelled on Drake and the Weeknd, without permission, that the track registers as AI generated at all. That was exactly the point, because without this conceptual register, ‘Heart on My Sleeve’ is totally unremarkable: just another track in the endless datasea of music you could listen to, but probably won’t.

2024 is the year automatic music generation broke because it was the year making this kind of unremarkable AI generated music became widely available to the public. Suno had launched right at the end of December 2023, and Udio followed just a few months later, both to considerable hype. According to one industry report from May 2024, ‘Udio’s users are now creating ten tracks a second on the platform.’ By July, Suno was claiming to have had 12 million discrete users. ‘Suno is building a future where anyone can make great music,’ the company said. ‘Whether you’re a shower singer or a charting artist, we break barriers between you and the song you dream of making. No instrument needed, just imagination. From your mind to music.’

Spend any time on these platforms and you’ll quickly notice that many of the ‘glitches’ and ‘errors’ that characterised previous efforts at automatic music generation are gone. The tracks Suno produces don’t sound ‘good’ exactly. Fidelity-wise, they’re similar to the kind of lossy mp3s you’d get on P2P networks like Limewire in the early 00s, which millions did. Presumably fidelity will improve with time, as the companies involved throw more data and processing power at the problem. Just a year after launch, Suno is already on v4. The key thing is that AI-generated music seems to have crossed the invisible threshold between shitty-but-interesting and more-or-less-plausible-as-music. Automatically generated music finally sounds ‘good enough’.

Good enough for some guy called King Willonius to intervene in the Drake / Kendrick Lamar beef with the genuinely funny Motown diss track ‘BBL Drizzy’, which he made using Udio.

Good enough for this track to get remixed by Metro Boomin, whose regular collaborators include Future, Young Thug, Travis Scott and Gucci Mane. Good enough for this remix to go viral on TikTok. Good enough for R&B artist Masego to use it as a backing track for an epic two-and-a-half-minute sax solo, and for someone to comment: “getting dissed in jazz is wild.” Fire emoji. 4k likes. Good enough for TikTok user carsonsmelliott to produce this amazing talk box cover. 804.1k views. 3245 comments.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

‘BBL Drizzy’ was probably the first track with an AI-generated hook to go properly mainstream, and to do so despite rather than because of how it was made. ‘BBL Drizzy’ isn’t conceptual art. It’s a meme, made by a comedian and “AI Storyteller” for the lols.

This is not a coincidence. The companies behind commercial AI music generation know just how well suited their product is for the meme game, and that there’s money to be made here. In an interview with one of the partners at venture capital firm Lightspeed Venture Partners, Suno co-founder and CEO Mikey Shulman explained that the company isn’t necessarily trying to compete with Taylor Swift on Spotify. Instead, it’s competing with the GIFs and emojis you send after a night out. Did Karen fall in a hole on the way to the bus stop? Whip up a song about it. Did Will improvise a great line based on a Rick Ross gag about Drake getting a Brazilian butt lift? Ditto. ‘We’re basically just as happy if you shared that song with your three college roommates and you all got a good laugh out of it’, Shulman explains, and ‘that’s where the song lives forever and ever’. Scaled up to billions of users, there’s plenty of money to be made even with an audience of three. Emojis, after all, are big business. But there's also ‘a lot in between Spotify and that three-person group text message’. Think of ‘BBL Drizzy’ as proof of concept.

Suno would take on the streamers if it could, though. Later in the interview, Shulman starts imagining a form of AI music generation that’s personalised in a similar way to a recommender engine, only instead of playing you a perfectly curated selection of existing music, it generates it. ‘Can we imagine a world where music is almost dynamically being created on the fly for our own personal tastes? ‘A hundred percent,’ he says. ‘And ultimately what generative AI will let you do is let you create that really, really micro niche that has only one person who really, really likes it… So I think that is yet another experience in music that doesn't exist yet today that we are excited about eventually being able to tackle.’

Writing about the culture industry of the 1930s and ’40s, Adorno railed against what he termed ‘pseudo-individuation’, whereby the deadening forces of standardisation and mass production were masked by inflating the significance of small differences. Commercial jazz was utterly homogenous, Adorno thought, despite the fact that no two solos are ever exactly the same. You are slightly different because you prefer Sidney Bechet to Benny Goodman. Adorno may have been a snob, but we could think of Shulman’s ‘Suno-individuation’ (sorry) as a kind of completion of this project: a machine literally designed to pump out infinitely variegated versions of the same pseudo music, each with an audience of one. Taken to its logical conclusion, the problem here isn’t so much the homogenisation of music culture as the total collapse of the kind of public sphere needed to sustain the concept of culture itself.

These two tendencies – towards good memes on the one hand and Suno-individuation on the other – are clearly in tension with each other. Memes work because of the shared culture that Suno-individuation would break down. ‘BBL Drizzy’ works because it’s funny to hear the genre conventions of Motown and classic soul (and maybe its political associations too: civil rights, Black power) brought to bear on a contemporary rap beef and a gag about cosmetic butt surgery. Or as one commenter put it, ‘my grandparents saw him performing this song live in 1974.’ 378 likes. When my son used Suno to make a song for his under-8s soccer team, it was funny because you don’t expect to hear a stadium-rock anthem, complete with guitar-hero solo, about that time the Monbulk Rangers beat Lillydale 2-0 away. Even he understood that.

AI generated lols are less offensive than the collapse of shared music culture into infinite personalisation. But the lawsuits currently being brought by Sony, Universal and Warner should probably give us pause for thought. The ‘big three’ record companies accuse Suno and Udio of ‘wilful copyright infringement on an almost unimaginable scale’. Their ‘wholesale theft of Copyrighted Recordings’ apparently ‘threatens the entire music ecosystem and the numerous people it employs. It also degrades the rights of artists to control their works, determine whether future uses of their works align with their aesthetic and personal values, and decide the products or services with which they wish to be associated.’

Now, this is a bit rich coming from the same companies who’ve profited massively, for instance, from the wholesale theft of the blues by white rock musicians and the globalisation of the intellectual property system as such. There is a telling moment 33 minutes into another podcast with Mikey Shulman, where the Suno founder suggests they test his product by making a ‘Chicago blues’ ‘about a sad AI wearing an Apple Vision Pro.’

For anyone with more than a passing knowledge of the blues, the result is definitely not funny. The lyrics are already terrible:

I'm a sad AI with a broken heart.

Where my Apple Vision Pro can't see the stars.

I used to feel joy. I used to feel pain.

And now I'm just a soul trapped inside this metal frame.

Oh, I'm singing the blues. Can't you see?

This digital life ain't what it used to be.

Searching for love, but I can't find a soul.

Won't you help me? Baby, let my spirit unfold.

But because the performance of these lyrics is ‘good enough’, because of the guitar’s characteristic twang and the unmistakeable Blackness of the voice, and because none of the podcasters are themselves Black, the whole thing smacks of AI minstrelsy. A stolen voice singing in a stolen tradition about a terrible product made by one of the biggest corporations in history.

Is this really what we want? All this investment, all this time and computation, earth minerals and energy, just for the lols, racist or otherwise? Is this who we want in charge of music’s future? A bunch of tech bros who seem not to know even the first thing about the music they’re appropriating and leveraging for profit? It bears repeating, for the unaware, that Suno’s founders met working for a company called Kensho, which specialised in automatic transcription for financial services companies. These people are not our friends.

Nevertheless, there’s something about Mikey Shulman’s horrendous blues that also suggests a way forward for anyone interested in thinking critically about automatic music generation now that it sort of works, now that it’s that much harder to jury-rig or détourne. In 2024, the specificity of most AI generated music is no longer really sonic. It’s not any particular sound, or artefact, or error, other than a general ‘lossiness’ which, as I say, is sure to improve anyway. Shulman’s blues ‘sounds’ AI generated because no self-respecting bluesman would be caught dead singing this trash.

We could say that critical engagement with the music-generation business after 2024 requires ‘shallow’ rather than ‘deep’ listening. This is a distinction made by the writer and theorist Seth Kim-Cohen. Deep listening, which is a term coined by Pauline Oliveros, ‘suggests something to be quarried, something at the bottom, a bedrock, an ore, a materiality that contains riches.’ Deep listening is what you might do when you listen to a recording of Howlin’ Wolf, and luxuriate in the ferocious sandpaper grain of his voice. Lifetimes have been spent in the real pleasures of listening this way. Now ‘imagine the same volume of listening attention’, Kim-Cohen says, only ‘instead of condensing it within a concentrated, narrow-gauge bandwidth,’ your listening ‘pools at the surface, spreading out to encompass adjacent concerns and influences that the tunnel vision of the deep model would exclude.’

That’s shallow listening: a listening that can hear Shulman’s blues and, rather than being impressed by the technical virtuosity, can tune in to the histories of racist dispossession it recapitulates and which have been embedded now in all the neural networks backed by venture capitalists keen to profit from automatic music generation as a sociotechnical system. This is the kind of kind listening AI generated music increasingly demands. Infinitely shallow listening for infinitely shallow music.